Gaspare Spontini's Opera Masterpiece

Callas's voice was noted for its three distinct registers: Her low or chest register was extremely dark and almost baritonal in power, and she used this part of her voice for dramatic effect, often going into this register much higher on the scale than most sopranos. Her middle register had a peculiar and highly personal sound"part oboe, part clarinet", as Claudia Cassidy described it and was noted for its veiled or "bottled" sound, as if she were singing into a jug. Walter Legge attributed this sound to the "extraordinary formation of her upper palate, shaped like a Gothic arch, not the Romanesque arch of the normal mouth". The upper register was ample and bright, with an impressive extension above high C, whichin contrast to the light flute-like sound of the typical coloratura, "she would attack these notes with more vehemence and powerquite differently therefore, from the very delicate, cautious, 'white' approach of the light sopranos."Legge adds, "Even in the most difficult fioriture there were no musical or technical difficulties in this part of the voice which she could not execute with astonishing, unostentatious ease. Her chromatic runs, particularly downwards, were beautifully smooth and staccatos almost unfailingly accurate, even in the trickiest intervals. There is hardly a bar in the whole range of nineteenth-century music for high soprano that seriously tested her powers." And as she demonstrated in the finale of La sonnambula on the commercial EMI set and the live recording from Cologne, she was able to execute a diminuendo on the stratospheric high E-flat, which Scott describes as "a feat unrivaled in the history of the gramophone."

De Hildalgo had the real great training, maybe even the last real training of the real bel canto. As a young girl—thirteen years old—I was immediately thrown into her arms, meaning that I learned the secrets, the ways of this bel canto, which of course as you well know, is not just beautiful singing. It is a very hard training; it is a sort of a strait-jacket that you're supposed to put on, whether you like it or not. You have to learn to read, to write, to form your sentences, how far you can go, fall, hurt yourself, put yourself back on your feet continuously. De Hidalgo had one method, which was the real bel canto way, where no matter how heavy a voice, it should always be kept light, it should always be worked on in a flexible way, never to weigh it down. It is a method of keeping the voice light and flexible and pushing the instrument into a certain zone where it might not be too large in sound, but penetrating. And teaching the scales, trills, all the bel canto embellishments, which is a whole vast language of its own.

Callas articulates all of the trills, and she binds them into the line more expressively than anyone else; they are not an ornament but a form of intensification. Part of the wonder in this performance is the chiaroscuro through her tone—the other side of not singing full-out all the way through. One of the vocal devices that create that chiaroscuro is a varying rate of vibrato; another is her portamento, the way she connects the voice from note to note, phrase to phrase, lifting and gliding. This is never a sloppy swoop, because its intention is as musically precise as it is in great string playing. In this aria, Callas uses more portamento, and in greater variety, than any other singer ... Callas is not creating "effects", as even her greatest rivals do. She sees the aria as a whole, "as if in an aerial view", as Sviatoslav Richter's teacher observed of his most famous pupil; simultaneously, she is on earth, standing in the courtyard of the palace of Aliaferia, floating her voice to the tower where her lover lies imprisoned.

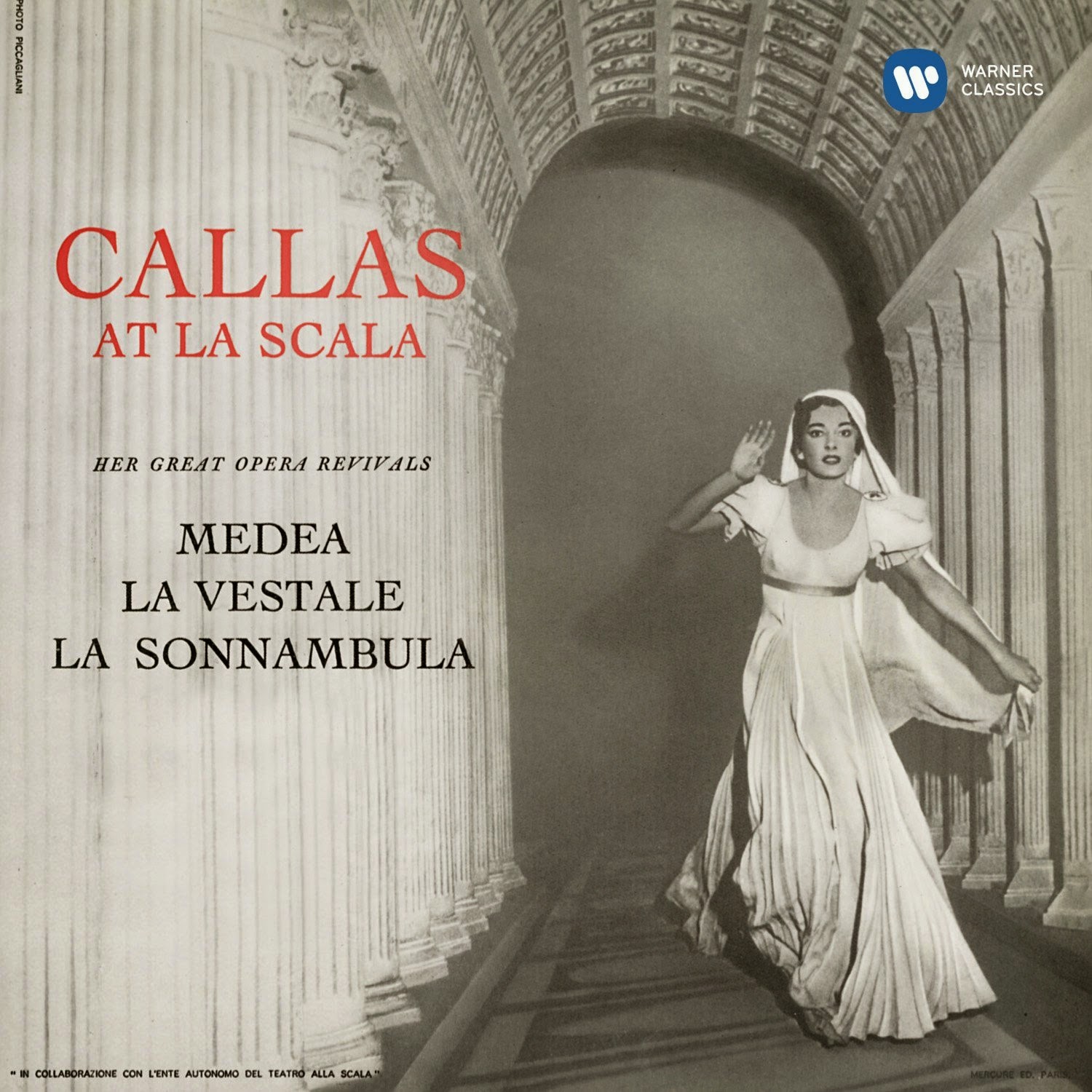

When Maria Callas opened the 1954–55 La Scala season in Spontini's La Vestale,the newly slender soprano had — under Luchino Visconti's directorial hand — fully developed the graceful body language and mesmerizing gestures and facial expressions that came to represent her physical acting style. The three-year, five-opera Callas– Visconti collaboration at La Scala began with this Vestale, a visually stunning production inspired by the paintings of Ingres, David and others. Its three acts were trimmed down to about two hours and ten minutes of music, given a dramatically intense reading by Antonino Votto and his cast.

Callas is in prime vocal estate; if the role of the vestal virgin Giulia doesn't allow her the virtuoso vocal feats she achieved in her bel canto repertoire, it gives her plenty of opportunity to pour out floods of passionate sound. The great aria "Tu che invoco" remained in her concert programs for years afterward, and it's thrilling to hear it in the context of the piece. Elsewhere, Callas makes the strongest possible case for Spontini's opera, as she did with those of Gluck at La Scala, through impassioned recitative and an instinctive mastery of the style; the text is delivered with clarity and ravishing word coloration.

Corelli made his Scala debut that night as Giulia's love object, Licinio, a curiously low-lying role for this particular tenor, but one in which his passionate vocalism nonetheless found plenty of opportunity to make an impression. Visconti reportedly found Ebe Stignani's static, matronly stage persona appalling as he endeavored to create vibrant theater. Stignani's singing, however, is far from static. As La Gran Vestale, the veteran mezzo delivers, a few squally high notes aside, a thrilling reading of her lengthy Act I scena.Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, as the Pontiff, offers his customary vocal and dramatic authority and occasionally wayward intonation. Supporting roles are well handled by baritone Enzo Sordello and leading-basso-to-be Nicola Zaccaria. From the vigorous overture on, the Scala forces deliver impressively, and the chorus shines as well in its substantial role.